Creating Your Own Story

We’ve all experienced it in a big action-adventure game: the enemy gives a speech, we get into a big boss fight, we take them down and move along. Sure, there might be some stakes to it all, and the characters might have some history, but it’s not a story in that we have any personal involvement. Two characters despise each other because that’s what the story tells us, but their reasons don’t extend to our gameplay. What we do in the game doesn’t matter. Just so long as we reach the next checkpoint of the story, things will proceed as planned.

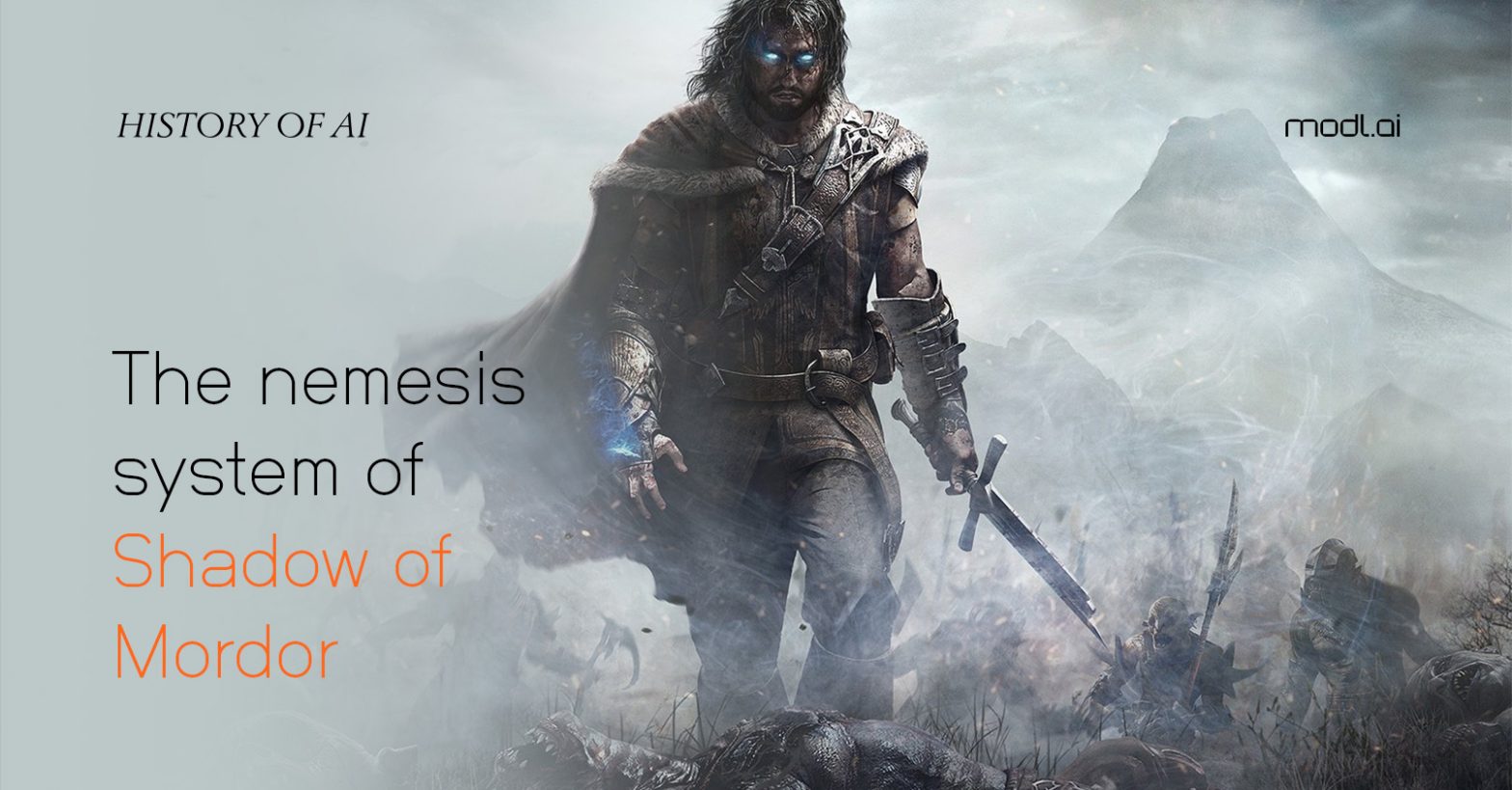

This is what made Middle-Earth: Shadow of Mordor so special. In this 2014 game by Monolith, your enemies learn who you are. They begin to taunt you and sometimes even hunt you down. You can learn their weaknesses and exploit them or struggle to find a gap in their defenses as you are forced to survive a grueling attack. All the while, the enemy taunts your inability to overcome them.

What made this game stand out is that when characters in games develop an affinity for players, it’s often fixed and predetermined: you can antagonize or romance characters in role-playing games such as Mass Effect, but those story outcomes are already baked into the game. The developers know every possible way the story can pan out long before you press Start. However, Shadow of Mordor achieves this procedurally. Meaning that the orcs you face are generated at runtime for you to face. This, in turn, means that your interactions with them and the stories you will tell about those encounters are unique to your playthrough. While their experiences may prove similar to some extent, no two players will ever have the same experience.

Meeting Your Nemesis

Shadow of Mordor was one of the most high-profile games to showcase the power of generated narrative: having characters that interact with the player and other game elements and use that to craft their own stories. An Uruk might defeat the player in combat, and once you have been resurrected, will mock you as you face them again. Conversely, they might run away and escape, only to remind you of your failure as they flee. Sometimes they can even come back from the dead, sporting scars and damage from their last encounter with you and demanding revenge.

All of this ran within the Nemesis system: in which each procedurally generated character developed their traits and personality and could subsequently establish themselves as a senior ranking officer in this legion of orcs. It means that one enemy that slipped away in an earlier fight could return hours later as a stronger, more powerful opponent, commanding a more significant part of Sauron’s army and being even more determined to bring you down.

The Story Continues

While it’s arguably the most high-profile case, it’s certainly not the first time AI has been used to build a narrative in games. Experimental games such as Facade by Andrew Stern and Michael Matthias pioneered AI-driven narrative in 2005. The player is visiting a couple’s house for drinks while they have a domestic argument that bubbles to the surface. The two characters, Grace and Tripp, respond to your inputs, and what you say to them can shape the narrative with various endings. It was a fantastic showcase of the potential of AI storytelling, even if sometimes the game didn’t know how to respond to what you were saying. Similarly, there was Versu in the early 2010s by Emily Short and Richard Evans: a narrative generation engine designed to create stories with multiple agents influencing the story as you experience it. It was then used to generate stories players could read and interact with in iPad games such as Blood & Laurels.

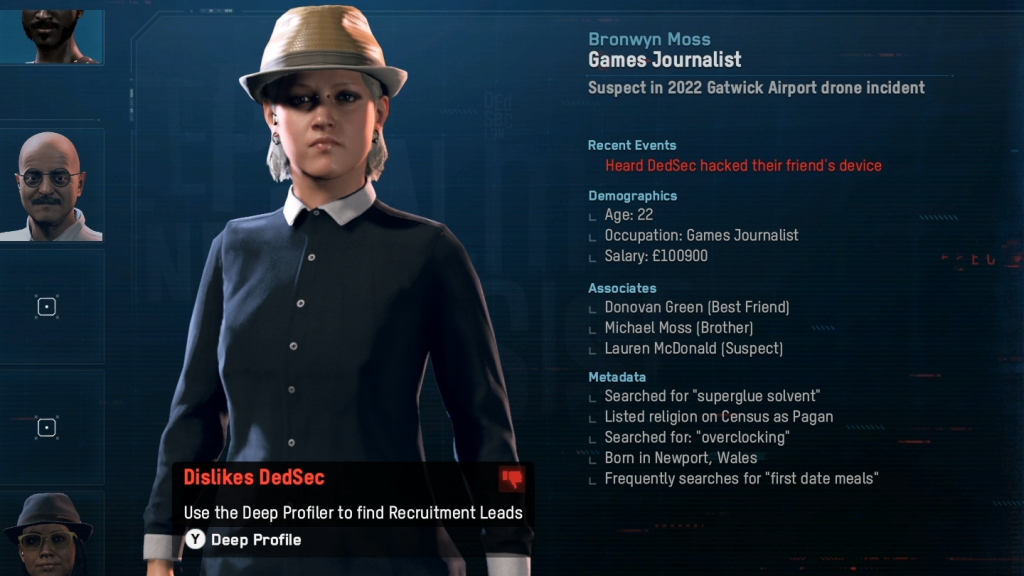

This is still an area with massive untapped potential. Recent games such as WatchDogs: Legion revisit this idea by creating unique characters whose stories and lives are influenced by your behavior in the game. From those stories, the game can create missions that – when completed – allow that character to become playable in your Dedsec rebellion. Once again, your playthrough is unique to you, and you develop connections to these digital characters. The level of complexity in these simulations is massive in scale, but it’s slowly becoming more manageable with better tools and an understanding of the potential of AI storytelling.

Adaptive storytelling is but one of many applications for AI in games. Be sure to follow along in our History of AI in games series to learn more about how artificial intelligence will continue to impact the videogames industry.

In the meantime, if you’re keen to learn more about some of the games mentioned in this article, check out the video on the AI and Games YouTube channel about the inner workings of Facade, plus an exclusive interview with many designers behind Watch Dogs: Legion.